A Hole So Big It Became the Sky is an interactive, intersectional, playfully serious, and dangerously provocative installation that collects and visualizes queer stories, experiences, and emotions that are otherwise unwritten, unspoken, deeply personal, and often suppressed. These are the stories that will forever haunt us until we collectively acknowledge and reframe them. They are queer hauntings from both the past and the future that must be harnessed in order to respond to the complex experiences of gender and sexuality in everyday life, in a society that strives to reorient itself toward more anti-colonial ways of knowing, rejecting Victorian constructs of morality and control, embracing queer theories as a basis for greater equality and respect. Guzman and Jefferies have blurred the lines between artist, academic, activist and audience while creating a show about emotion, trauma… affect.

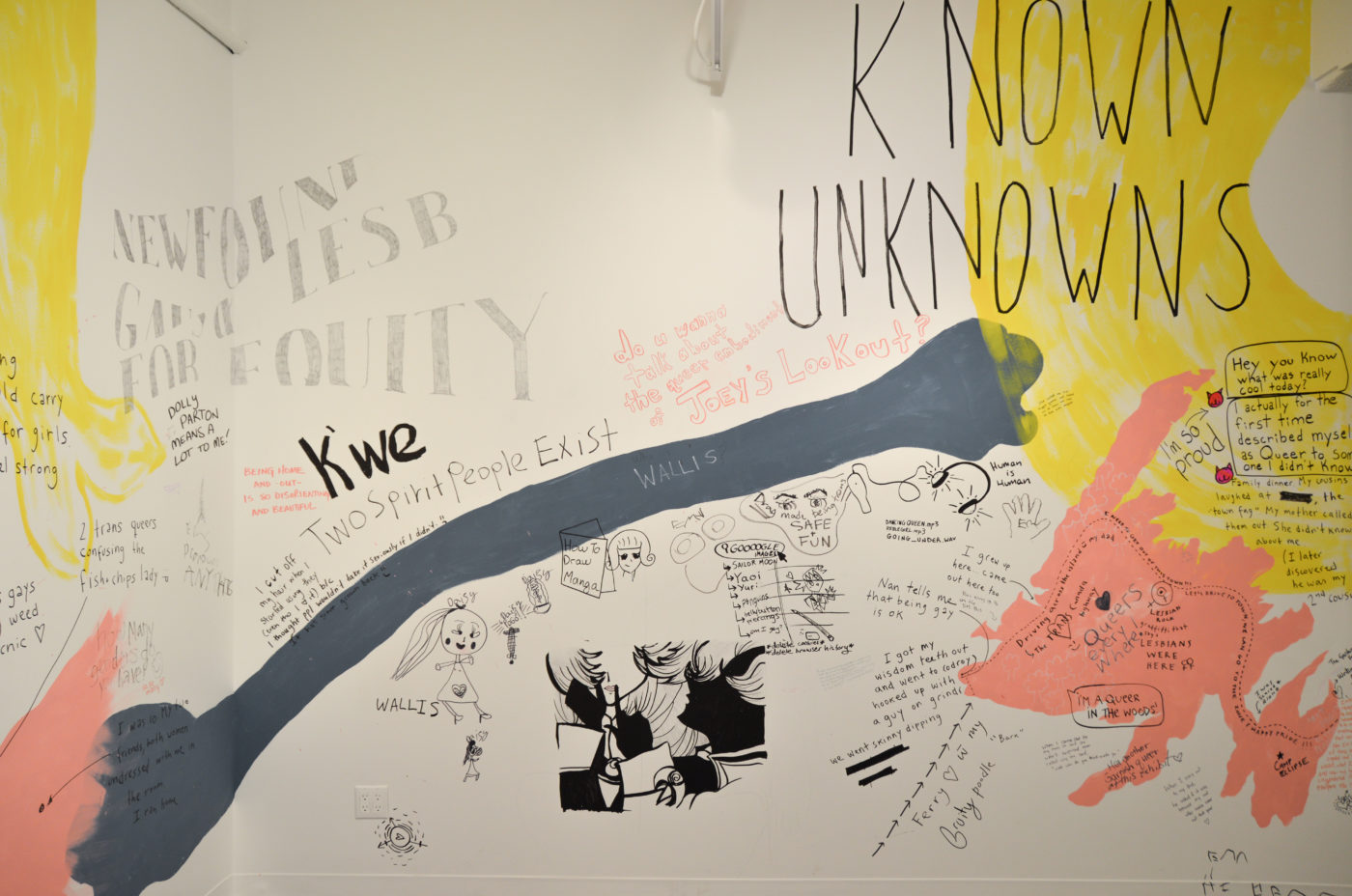

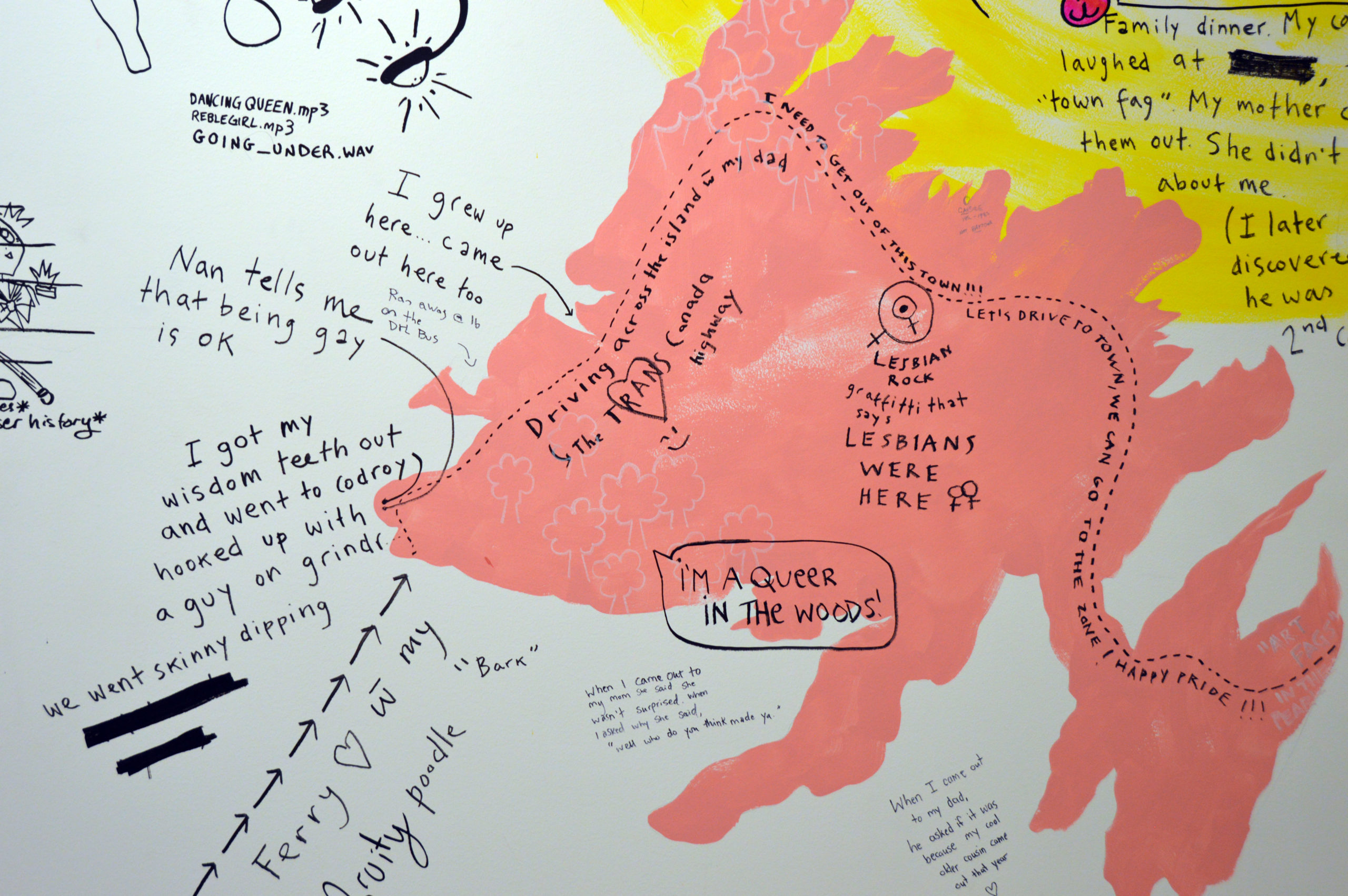

What does it feel like to be trans, gay, or non-binary in Newfoundland and Labrador? How do these feelings influence one’s attachment to place? Through a set of three public workshops on queer drawing (strategies of drawing, drawing from memorabilia and ephemera, and drawing memories and place), Guzman and Jefferies collected a diversity of memories that would form the basis of the mural. Participants were asked to bring in objects, maps, and experiences, and through the act of collecting, sharing, and drawing, many new stories emerged. What did coming out feel like for you? How was your life, your friends, your family, and your community affected? Was it traumatic? How has affect challenged your place within the 2SLGBTQI+ community?

Daze Jefferies is already established as a quietly fierce leader in protecting and publicizing queer and trans histories in Newfoundland and Labrador, using folklore methodologies to collect and archive, and exploring decolonial and artistic approaches to analyze and reveal the affect from such stories and experiences. Using music, poetry, found objects, and soundscapes, Jefferies has dedicated her life to developing ideas on queer archiving, often through the framework of “feeling fishy”. Where are the lives of rural trans women documented, women who “migrate across land, ocean, and sex” (2018, 10) through diasporic NL? As Jefferies explains, beyond oral narratives, trans stories from this place have recently been embedded in letters to MHAs, doctor’s notepads and medical records, and St. John’s graffiti. They are slippery and ephemeral. Longer histories of gender and sexual diversity have been afflicted by colonial violence, and thus we need to decolonize our archival methodologies. Some of Jefferies’ “fishy” objects are currently on display at The Rooms, in her Future Possible showcase Imperma (2018).

Coco Guzman frequently uses on-site mural-like drawings to express their ideas about gender, sexuality, and protest. We can see this in Ver o no ver (To see or not to see) in the XIII Havana Bienal (2019), a bathroom installation that incorporates many bathroom-sign-like drawings. These drawings are also part of the Genderpoo (2008- ) series, and are intended to playfully push the viewer to question who is silenced or erased from the public sphere through the cis-gendering of public toilets. In addition to the visualization of queer and critical theory through art, Guzman frequently highlights the issue of protest, demonstration, and power in society, as shown in their larger-than-life mural The Demonstration / La Manifestación (2016). Guzman successfully assists us as we continually question the role of Pride, demonstrating the interdependencies of celebration and protest. As with Jefferies, Guzman’s overture focuses on the ways we remember, a performance of what queer theorist Heather Love calls “feeling backward”. Again, it is more than writing history; it is a way of documenting trauma, affect, and hauntological fears onto queer bodies.

Together, Guzman and Jefferies blend academic rigour and artistic vision, visualizing queer theory, and engaging their audience in provocative thought. The format of this show is not entirely new, but rather it is reflective of queer histories such as The Celluloid Closet, and Paris is Burning – two of the most influential 2SLGBTQI+ documentaries/archives in acknowledging and demonstrating the power of affect on suppressing but then creating community and activism over time. As explained by Love, it is about “a trauma of queer spectatorship – most often articulated as an isolated and uninformed viewing of negative images of homosexuality” (Love 2009, 15). The layering of oral history and art however, creates the sense of a group conversation, critiquing negative images while revealing communitas and spanning the previously un-spannable space between affect and politics. When we can feel that we are not alone, we begin to know that we were never alone, and such transphobic and homophobic experiences can no longer haunt us.

At the opening reception: The mural wraps around the room without a clear direction. There are paintings on the walls, with snippets of queer history – news stories that Jefferies collected from the Centre for Newfoundland Studies. These are juxtaposed with personal stories from the participants, stories that are added to throughout the installation. Excerpts of interviews – queer and trans oral histories recorded by Jefferies – are broadcast on a loop. These stories intermingle with the conversations of the viewers, making it difficult to tell which voices are recorded and which ones are new. Through this intermingling, it is impossible to not reflect on one’s own story, perhaps raising suppressed memories of harassment or fear… perhaps raising memories of creating harassment and fear.

Beneath scrawled text and hectic drawings, the ghostly forms of giant mermaids swim across the walls. One of Guzman’s signature images – the moustached mermaid – resonates in Newfoundland and Labrador. Mermaids hold a special place in Jefferies’ work as well. She cites the first recorded encounter by colonizers with mermaids in 1610 at the mouth of the Waterford river, where the three fishy women were beaten by sailors until they disappeared. Jefferies frames these aquatic beings as “queer ancestors”, living in between worlds and forcibly submerged since colonization.

A Hole So Big It Became the Sky is an immersive experience that tackles one of the largest failures of academic and queer activism: introducing your ideas to an audience that expands beyond your core supporters – engaging non-queer individuals so that they can better hear and understand the everyday realities of the queer other. Opened during Peace, Love and Pride week, the show is particularly well timed. While Jefferies and Guzman use the mythological mermaid figure to address gender diversity and its colonial erasure, St. John’s Pride honoured the Merb’ys and the NL Beard and Moustache Club as Community Group of the Year 2019. Merb’ys and mer-people… the imagery of both artists and organizations now wends its way into NL popular culture.

Across our diverse, 2SLGBTQI+ community, we have found unity through a gender fluid, non-binary, and body positive folkloric image. The assemblage of mermaids, mermen, and mer-people is not only a unifying symbol across the spectrum of gender and sexuality in Newfoundland and Labrador, but it is also a symbol that brings us into better dialogue and understanding with non-2SLGBTQI+ individuals. It is a playful symbol that encourages everyone to stop, think, and – perhaps most importantly – listen.

- Cory W. Thorne, coryt2@mun.ca

Photos from the exhibition: “A Hole So Big It Became The Sky” created by Coco Guzman & Daze Jefferies, with community participation. Summer of 2019.