Webs of Care | Essay by Valerie Webber

I am not an artist. I am perhaps what one could call art-adjacent. If I’m involved, I’m often the one taking direction in the background, operating in the periphery: stage management, grunt work, prepping before or cleaning up after the show. It’s the kind of helping-labour that I thrive on. One way I have been called to participate in queer art – with its own particular skillset, its own particular quality of presence – brings me to think about care.

This way is stapling.

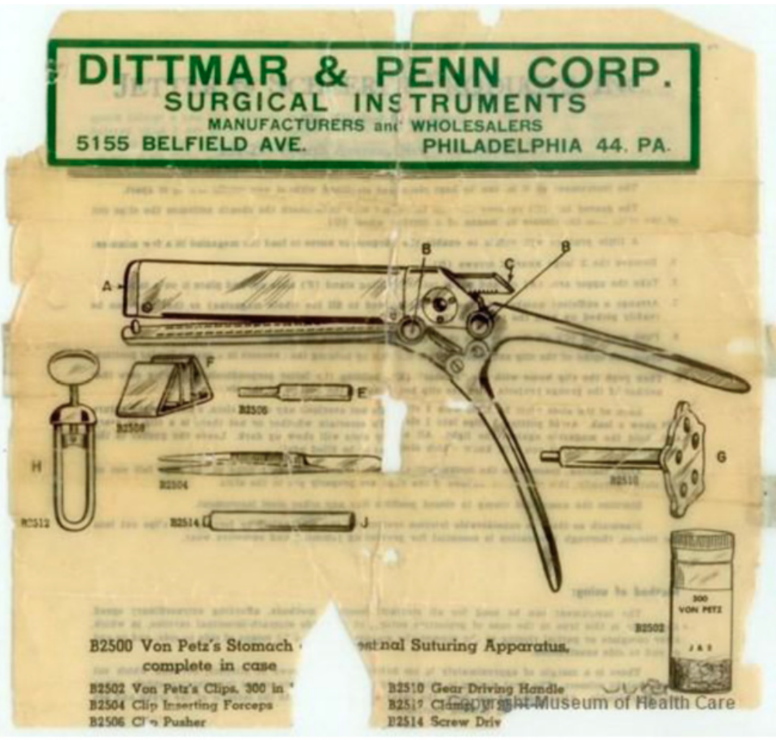

The surgical stapler1 was invented in 1908 by Hungarian surgeon Hümér Hültl and medical instrument designer Victor Fischer, as a faster and more sterile method of resection, transection, closure, and anastomosis2. The original model was inconvenient – it took two hours to assemble, and the staples had to be individually loaded with tweezers. Hültl’s student Aladár Petz improved upon the design, and in 1921 (after trials on dogs and cadavers), launched what would become the most widely used style for several decades.

3

3

In 1958 American surgeon Mark Ravitch visited the then-Soviet Union on a Cold War-era goodwill trip and witnessed the use of stapling during lung surgery. Fascinated, he managed to purchase several models at a factory store, importing the technology to North America.

The multinational that currently dominates surgical and skin stapler production is Covidien. An unfortunate name to have at the moment, perhaps; but when I visited their site, the homepage highlighted ventilator sales, so one can assume their titular association with the current pandemic is actually working out ok for them.

4

4

My first encounter with medical staples was waking from surgery to find them in my body. I had gotten classic stitches before, after a minor altercation with a kitchen knife in a soapy sink. But this time I had snapped my elbow in half – the olecranon, to be precise – and they needed to make a 10cm incision in order to fetch the detached piece of bone and nail it back into place.

The surgeon told me staples are ideal

for closing joint wounds

as they enable more flexibility

throughout the healing process.

The drunken bike accident that led to my elbow break was not quite the end of my drinking, but it was a significant event leading up to it. By the time the staples were removed, the bone re-fused, the skin sliced back open, and the pins pulled out, I had drunk what remains my last drink. A procession of care followed. New ways of perceiving what it meant to tend to myself, and inevitably, to tend to those around me. Staples epitomize much about the form of care I embarked on: holding myself together with firmness and flexibility, cultivating and curating a tough but spacious container in which to sort through my suffering, closing inward on myself in order to heal enough to finally focus on something other than myself.

It was years later that I would be living in St. John’s, on the phone with Jason Wells, who explained that a performer was coming to town and needed help stapling their head for their piece. Jason thought of me as capable of being sanitary and professional, calm and calculated. I admitted I had no such exact experience, but felt intrigued and comfortable and would be happy to try – I’d even bring my own nitrile gloves.

To impose on the body of another in this way is a special kind of care. It is not offered, but requested. It is defined and articulated solely by the recipient. It has elements that are deliberate and specific, but also vague and atmospheric. I was enthusiastic to help realize someone else’s vision, without needing to know or understand anything about it other than how to avoid causing harm, as they defined it. I was enthusiastic to be called upon to serve a stranger’s body. And I was enthusiastic to discover if I could exude the miasmic cloud of composure that would be conducive to the work, while keeping tabs on the relentless reality of the call time.

I won’t pretend to have anything meaningful to say about Hollow Eve’s performance art generally, or the specific performance they gave at the Retroflex Cabaret5, wherein they spent the evening tethered from an array of body staples to a surrounding monofilament web by tense elastic cords. As a spectator, it was mesmerizing and heart wrenching. The room was rapt, as tense as the elastics pulling on Hollow’s skin, as tender as the fleshy layers beneath. That said, I don’t have any particular analysis as to why it was so impactful.

“Since their development in1908, surgical staplers have been used […] in efforts to divide hollow viscera…” 6Photo: Jason Wells

Like I said, I’m art-adjacent: appreciative, but not versed in the literature and language of critique, so I haven’t much to offer beyond my subjective impressions. My focus now, as I reflect many months later, is drawn to something Hollow shared with me that day, and which I have also read in interviews7: that after shows involving a lot of stapling or piercing, they take breaks from performing. That they take iron supplements to replenish the blood loss.

For many of the uninitiated, it might be easy to assume that any activity from which we need to actively heal cannot itself be healing.

I say the uninitiated because I think that anyone who has even a passing experience with BDSM knows that this is not true: that putting the body through something can be intensely healing and intensely pleasurable, intensely extravagant and intensely pragmatic.

Skin stapling illustrates the seeming contradiction: a tool, a task, intended to pull one back together, to heal/seal/fix/&close, but now done to skin that is not yet broken, actually wounding (in the traditional sense of the word) rather than healing (in the traditional sense of the word). Yet as I fingered the tough skin of Hollow’s skull, plotting each staple’s destination, summoning with each firing two tiny puncture wounds – most dry, some eventually serving up a little mouthful of blood – I felt a sturdy yet exhilarating mixture of action and attentiveness, provocation and receptivity, honour and responsibility (the ability to be responsive). In short, I felt some part of them was in my care.

I tend to you through

the tiny wounds.

Help me hurt-heal yourself.

Photo: Jason Wells

Is this kind of care queer? I ask, but also wonder in the same breath if there is any purpose or value in the question. I’m exhausted by the academic use of queer this and queering that and what feels like the overactive deployment of queer as a prefix disconnected from anything to do with how people live their lives. Voicing the words “queer care”, like any other “queer fill in the blank“, can feel like a vapid or panicked attempt at ownership, or a tired way to try and sex up a concept, rather than something that makes any meaningful moves upon an idea. Musing over whether or not something is queer feels like I’m just adding to the wealth of cultural production about queerness, when I’d rather just see stuff that is super fucking queer for queers without even needing to be labelled as such.

But, I also believe that queer lifeways, like so many lifeways that are maligned or pathologized or ridiculed or obliterated, have something to offer, conjuring possibilities where there seem to be none. Maybe this is why the question flows from me.

The notion of stapling as an expression of queer care comes to me because of how it embodies the paradoxical aesthetic and affect of the service top.

I don’t mean to conflate BDSM and queerness. Obviously there are kinky hets and vanilla queers. But I know that amongst queers, broadly defined, I am less likely to have to explain some reference to kink. Like, because I’m writing this for queers, I’m not bothering to define ”service top”. And during the endless Zoom meetings that now populate my week, it is always queers who knowingly nod to the soothingly symmetrical display of BDSM equipment adorning my back wall. For better or worse, queerness and kinkiness cohabitate a pocket in the Venn diagram of the “sexually nonnormative”.

And I personally associate my queerness and my kinkiness, among other facets, to my faith in pain (psychic/spiritual/physical) as both a precursor and a conduit to restorative work, and my belief in care as a particular relationship to that pain: one that neither runs toward nor away from it, but which cradles, or even cultivates it – with the right dosage and distance – for the purpose of a future form and a greater good.

Every tiny tether

in your skull

binds you to you and to us,

this flexibility this tight tenderness

indulging and displacing the body.

Photo: Jason Wells

Accountability also inheres in the care of stapling. To protect the person you are stapling from infection or other complications requires that you protect yourself: wearing gloves, using disinfectants, practicing universal precautions. I must take responsibility for myself, ensure I have and do what I need to create an antiseptic zone, as a prerequisite for and component of offering this care to another. Perhaps now more than before we recognize how it is compassionate and ethical to conceptualize ourselves as both potential victims and vectors8 of infectious pathogens (a notion of mutual responsibility that I wish would be mobilized towards striking Canada’s discriminatory HIV non-disclosure laws. A politics of care can never develop out of demonization and blame). Something in the act of putting on my gloves, swabbing the skin: it is care in the moment and care that considers a future, carving out a space to safely make a wound.

The next time I took up the stapler following the Retroflex Cabaret, it would be under conditions of even greater infection caution, bordering on infection-anxiety. This time I was helping Kailey Bryan aka \garbagefile, (who I get to date, to my great honour and deep delight9). They were creating a drag art film10 where they are stapled and corseted with ribbon, before writhing on the floor with a slice of cake in an unholy display of decadent filth.

Image: Still from Red Velvet

We shot the video twice, once in the first days of local COVID-19 rumblings, the second time a week later, when strict lockdowns were imminent. A small team, but in a small room, we circled one another with hyper-awareness of this news, not quite yet real but not imagined. We washed our hands. We wiped down the tripods. Everything done for ourselves is a doing for one another.

I slip on my gloves, slide a (now cherished) alcohol swab down a strip of Kailey’s back and legs, drawing a mental line of where the punctures will go. I try to administer a gentle but dauntless touch that will provide assuring counterbalance to the bite of the staples. A piercer friend once told me the key to that work is exuding confidence. Once you start breaking skin, you can’t second guess.

Image: Still from Red Velvet

I’ll bet the surgeons who opened my arm

were told the same

by their teachers.

Timidity isn’t a gift.

Kailey’s pale skin tenses under my nitrile fingers, readying itself for keen feeling, seeming to harden the more that it reddens. Each staple punctures their flesh, the two ends pinch to meet amidst the dermis. The meat curls it in on itself just a little. Their body settles in to this place.

Kailey has shared that they have an exacting vision for their practice, knowing precisely what they want to create and how they want it to look. The acuteness of this vision is part of why we shot the video a second time. They note how this laser focus can be a curse, especially when the world is on pause and everything is that much harder to make. But the kind of care one can offer, when you know to place the staple right here, to lace the corset like so, is of such a rare quality. I am grateful for the dynamic that develops out of being gently but unequivocally told what is needed and doing one’s best to give it. It is an enriching and energizing opportunity for reverence: to the one we care for, and to the notion of care itself.

The staples must be removed. Using a special crimping tool, I pinch the straight back of each one, retracting it by bending its arms back like little wings. I drop them lightly into a tray with a satisfying plink. Kailey’s skin shows signs of the experience; red blushes, tiny rivulets of blood. I run another alcohol swab along the length of their body. I place it in the tray.

So we hold ourselves that we can hold others, who hold us in return with the power of their trust. The net unfurls. Falling upon it, we fuse into it.

We aren’t in bubbles, we’re in webs.

11

11

1Gaidry, A.D., Tremblay, L., Nakayama, D., & Ignacio, R.C. (2019). The History of Surgical Staplers: A

Combination of Hungarian, Russian, and American Innovation. The American Surgeon, 85(6): 563-566.

2Resection: removal of part of an organ; transection: crosswise closure or incision; closure: closing an incision; anastomosis: the surgical joining of organs, especially tunnel-like parts e.g. intestines.

3Petz Clamp image from the Collection of the Museum of Health Care at Kingston:https://mhc.andornot.com/en/permalink/%20artifact3487

4Covidien stapler images from: https://www.medtronic.com/covidien/en-us/products/surgical-stapling/skin-staplers.html & https://www.medtronic.com/covidien/en-us/products/wound-closure.html

5Event description from: https://easternedge.ca/retroflex-cabaret/

6Gaidry et al. p.563

7Cammack, R. (2019). Stretching, Piercing, and Stapling with Hollow Eve, Gloss Magazine, November 8: https://www.glossmagazine.net/2019/11/stretching-piercing-and-stapling-with-hollow-eve/

8Battin, M.P., Francis, L.P., Jacobson, J.A., & Smith, C.B. (2008). The Patient as Victim and Vector: Ethics and Infectious Disease. Oxford University Press.

9Such ambivalence around whether or not to include this. Is it relevant? Arguably, for a text on intimacy and care. But is it, heaven forbid, unprofessional? Arguably, and therefore all the more reason to include it.

10Red Velvet, 2020: https://vimeo.com/407377166

11Staple image from: KimvdLinde (2010), licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.