Response to Diary of a e’pite’ji’j: hypervigilant love + Big ‘Uns

Response to Diary of a e’pite’ji’j: hypervigilant love + Big ‘Uns

**Trigger Warning**: the following response to Diary of a e’pite’ji’j: hypervigilant love mentions descriptions of colonial violence against Indigenous Women, Two Spirit folks, gender non-conforming individuals and girls— the work in this exhibition is personal and specific to experiences of the artist. Navigating this conversation has been difficult, however this written response honours with sensitivity the consent and care of the reader.

– Wela’lioq | Thank you all. Love Emily.

2019 has been an exceptional year for programming and community engagement at Eastern Edge. This success can be attributed to the efforts of RetroFlex, a year-long curatorial project established by Kailey Bryan, Jason Penney, and Jason Wells. Through a selection of exhibitions, film screenings, performance interventions, artist talks and residencies, Retroflex procures space for the queer histories and legacies of so-called Newfoundland and Labrador. The final two photography-based exhibitions that elevate and unabashedly bring to the forefront the voices of our Indigenous trans, gender non-conforming, queer and Two-Spirit relations are Diary of a e’pite’ji’j: hypervigilant love by Jude Benoit and Big ‘Uns by Dayna Danger.

In fractal waves of nostalgia and grief, Diary of a e’pite’ji’j: hypervigilant love mediates the experiences of Benoit’s youth in an installation like their childhood bedroom from the West Coast of Ktaqamkuk; “E’pite’ji’j” is the mi’kmaw word for “young girl” and speaks to Benoit’s experience of growing up as a queer trans Indigenous youth and the fluidity of their gender.

A crumpled blanket surrounded by pillows, a lamp, diaries, and a karaoke machine sit in the corner of the rOGUE Gallery– fishnet stockings, garbage bags, and tissue paper trapped in a net containing debris of the ocean dangle overhead. From this fishing net emerge constellations of garbage like condoms, tampons, empty pill bottles, lighters, and objects that likely were found on the floor of their bedroom. These intimate objects sprawling from the net create what Eve Tuck and C. Ree refer to in their Glossary of Haunting as a suspended ceiling: “Ceilings which leak. Ceilings which stare back. Ceilings which crash down.” We are immersed in the memories, emotions, and ghosts of Benoit’s past.

Suspended in the centre of the gallery is a mobile of disposable photographs – a series that revisits moments and locations in Benoit’s past where they personally experienced fear and panic from being alone with another individual. The materiality of these photographs amongst the debris echo the disposability that Benoit has felt in, and as a result of, these situations. Each photograph is accompanied with a caption written on the back, one quote says:

“I picture myself at the bottom of every ocean, lake, pond, and river.”

Not only will viewers reckon with these personal experiences, but how “water is also haunted, polluted with the violence of colonial histories.” The murky atmosphere of this undersea bedroom was fabricated by Benoit to disclose the intimate violence they have experienced throughout their life, and to draw attention to the systemic and historical violence against Indigenous people. The constant anxiety of danger is ever present for women, trans folks, gender non-conforming individuals, and Two-Spirit people—this is the hyper-vigilance that Benoit contends with in their life.

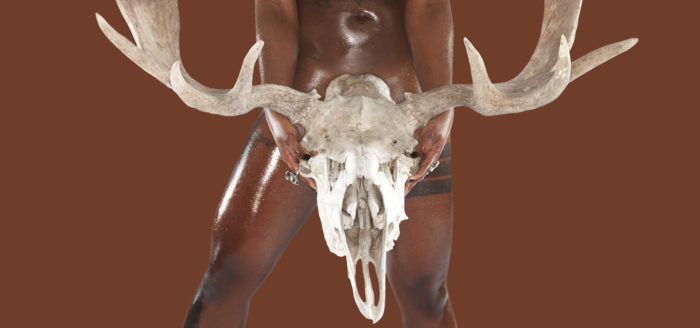

While the installation and poetry of Benoit calls attention to their own personal traumas and experiences at the hands of colonialism, the tone dramatically shifts to the exhibition in the Main Gallery by Dayna Danger – Big ‘Uns synthesizes these feelings of vulnerability in a way that commands the entire gallery to witness the erotic sovereignty of the individuals photographed. Big ‘Uns is an ongoing portrait series that seeks to return agency to queer folks, women, Two Spirits and gender non-conforming people who systematically have had a lack of power over the representation of their bodies and sexualities.

This iteration of the project consists of six large format portraits with gazes that confidently peer out into the space. Each individual is glistening with oil and have been paired with a set of animal racks in the form of a strap-on. When looking at the towering portraits, I think of animals that lock antlers in conflict, mating, or defense, which brings an element of confrontation that electrifies and erotically charges the gallery—these antler strap-ons are wielded in opposition to imposed acts of colonial violence on women and gender non-conforming people.

Embedded in the language, imagery, and theories of sport hunting, we encounter “the sexualization of animals, women, and weapons, as if the three are interchangeable sexual bodies in narratives of traditional masculinity.” By collaboratively braiding together aesthetics from mainstream porn and sport hunting magazines, these portraits created between Danger and the individual being photographed counter these narratives perpetrated by settler colonialism. In their work, Danger considers the line between what is objectification, and what is empowering. A key element of that empowerment is the ongoing consent practices and protocols developed between Danger and the individuals they collaborate with.

Danger says “the antlers and the tension that they cause, allude to the many factors that we must contend with in order to have healthy relationships, positive self-image, and, of course, sexual relationships… by repossessing the antlers in this way, we aim to demonstrate a reclaiming of power for women, Trans and gender non-conforming people and how we choose to be seen.”

These portraits manifest the queer futurities and histories of our kin while acknowledging the power of previous queer generations. For people to walk into a space and see themselves reflected is an important part of the work that Danger and Benoit do. Writer Lindsay Nixon said it best: “Danger heals non-binary Indigenous gender and diverse sexuality where there seemed to be no worlds left for Two-Spirit peoples.” These two exhibitions are the manifestation of those worlds and show the beauty and resilience of these people, this work is for them. You are seen and you are loved.

-

- Eve Tuck and C. Ree, “A Glossary of Haunting”, in Handbook of Autoethnography, eds. Stacy Linn Holman Jones, Tony E. Adams, and Carolyn Ellis (California: Left Coast Press Inc, 2013), 654.

- Sonja Boon, “Water: Flooding Memory“, in AutoEthnography and Feminist Theory At the Waters Edge: Unsettled Islands, compiled by Sonja Boon, Lesley Butler, and Daze Jefferies (Switzerland: Palgrave Pivot, 2018) 62.

- Linda Kalof, Amy Fitzgerald, and Lori Baralt, “Animals, Women, and Weapons: Blurred Sexual Boundaries in the Discourse of Sport Hunting”, Society & Animals 12, no. 3 (2004): 237.

- Lindsay Nixon, “Queer and trans NDNs love to talk about sex with their kin, bb” Let’s Talk About Sex, bb (Kingston: Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 2019) 67.

Emily Critch is an artist and curator with settler and Mi’kmaq ancestry from Corner Brook, Ktaqamkuk (Newfoundland). She received her BFA in Visual Arts from Grenfell Campus, Memorial University of Newfoundland (2018), and her art practice revolves around the anxieties surrounding the dimensions of preservation, loss, and care. Primarily using photographic printmaking, Emily considers how we care for our histories, kinships, and our relationships to place through storytelling and land. She has exhibited her work provincially and internationally at venues such as Grenfell Art Gallery, The Rooms, Eastern Edge, and Gatehouse Gallery in Harlow, England. Emily has recently participated in the inaugural Momus Emerging Critics Residency in partnership with Concordia University, and has completed residencies with the Corner Brook Museum and Archives and St. Michael’s Printshop. She has been the recipient of several awards, including a Professional Projects Grant from Arts NL, the Ellen Rusted Award for Print Media, the Reginald Shepherd and Helen Parsons Shepherd Award for individual artistic development.

Dayna Danger is a visual artist, organizer and drummer. Danger holds a MFA in Photography from Concordia University. Through utilizing the processes of photography, sculpture, performance and video, Danger creates works and environments that question the line between empowerment and objectification by claiming the space with their larger than life works. Ongoing works exploring BDSM and beaded leather fetish masks negotiate the complicated dynamics of sexuality, gender and power in a consensual and feminist manner. Danger has exhibited their work nationally and internationally. Danger is a 2Spirit, Métis – Anishinaabe(Saulteaux) – Polish, hard femme who was raised in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Treaty 1 territory, homeland of the Métis.

Jude Benoit is a Two-Spirit artist from the Kitpu clan. They have fought for rights and better support systems for the 2s/trans community for over a decade. They are also a fierce land and water warrior whose only words on reconciliation are “land back”. Their work has been fluid over the years (much like their gender), starting with poetry and spoken word when they were a teen, to then helping other queer youth perform and write their own stories by producing shows, open mics, and workshops. In their off time from being an artist, community organizer and downright badass you can find them working as a barista, reading tarot cards and ignoring their obvious burnout.